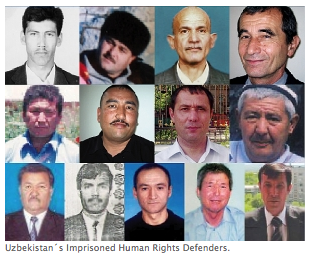

Uzbekistan's Imprisoned Human Rights Defenders

Friday, May 13, 2011 at 10:49PM

Friday, May 13, 2011 at 10:49PM  Human Rights Watch calls on the Uzbek government to immediately and unconditionally release all wrongfully imprisoned activists, several of whom suffer from serious illness and at least seven of whom have been ill-treated or subjected to torture in prison, and urges Uzbekistan's partners to make their freedom a top priority in their dialogues with the Uzbek government.

Human Rights Watch calls on the Uzbek government to immediately and unconditionally release all wrongfully imprisoned activists, several of whom suffer from serious illness and at least seven of whom have been ill-treated or subjected to torture in prison, and urges Uzbekistan's partners to make their freedom a top priority in their dialogues with the Uzbek government.

Uzbek authorities continue to hold in prison at least thirteen human rights defenders for no reason other than their legitimate human rights work. They are: Solijon Abdurakhmanov, Azam Formonov, Nosim Isakov, Gaibullo Jalilov, Alisher Karamatov, Jamshid Karimov, Norboi Kholjigitov, Rasul Khudainasarov, Ganihon Mamatkhanov, Habibulla Okpulatov, Yuldash Rasulov, Dilmurod Saidov, and Akzam Turgunov.

Many other civil society activists, including independent journalists and political dissidents, are likewise serving sentences on politically motivated charges, such as Yusuf Jumaev, a poet and political dissident sentenced to five years in a penal colony after calling for President Islam Karimov's resignation in the run-up to the December 2007 presidential elections. According to his family, Jumaev continues to suffer ill-treatment in prison and is in very poor health. His family reported that in June last year, Jumaev was subjected to repeated beatings by his cellmates, but prison authorities ignored his requests to be moved. Then, in late October, without explanation, prison authorities made Jumaev stand out in the cold and in the heavy rain for approximately two hours.

Some of the activists featured here worked to shed light on the May 2005 massacre in Andijan, others worked to protect farmers' rights, document torture, and expose corruption and religious persecution. They are all in prison as a result of daring to take on such work.

Solijon Abdurakhmanov

Abdurakhmanov (b. 1950) is a Karakalpakstan-based independent and outspoken journalist who has written on sensitive issues such as social and economic justice, human rights, corruption, and the legal status of Karakalpakstan in Uzbekistan. He worked closely with UzNews.net, an independent online news agency, and also freelanced for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Voice of America, and the Institute for War and Peace Reporting. He also is a member of the human rights group "Committee for the Protection of Personal Rights."

Traffic police arrested Abdurakhmanov on June 7, 2008, when they stopped his car, allegedly to check his identity, and claimed they found drugs on the underside of his car. Abdurakhmanov denies knowing about or having anything to do with the drugs. His brother, Bakhrom, a lawyer who also represented him, and fellow human rights defenders believe that the police planted the drugs. During the pre-trial investigation, the authorities primarily questioned Abdurakhmanov about his journalistic activities.

On October 10, 2008, following a trial that failed to meet fair trial standards, Abdurakhmanov was found guilty of a fabricated charge of selling drugs and sentenced to 10 years in prison. The sentence has been upheld twice on appeal. Abdurakhmanov is currently held in prison colony 64/61 in Karshi.

Farkhad Mukhtarov, another human rights activist who had earlier served prison time with Solijon Abdurakhmanov in Karshi before his release in December 2010, told Human Rights Watch that Abdurakhmanov had been charged with numerous violations of the prison regime to make him ineligible for amnesty or early release. These alleged violations included ‘not marching correctly' or ‘not sweeping up his cell', even though prison authorities have never provided him with a broom.

According to Abdurakhmanov's relative, in February 2011, Abdurakhmanov gave his lawyer a written complaint to submit to the Supreme Court, but the document was confiscated by prison authorities who claimed they would send it themselves. As of this writing, however, there has been no reported outcome and it is not clear if the complaint was submitted.

Azam Formonov

Formonov (b. 1978) was an active member of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan in Gulistan, in Syrdaryo province, who along with fellow defender Alisher Karamatov monitored violations of social and economic rights, in particular the rights of farmers and the disabled.

Formonov was arrested on April 29, 2006 and sentenced on June 15, 2006 to nine years in prison by the Yangier City Court on charges of attempting to blackmail a local businessman. He was tried without the presence of either his attorney of choice or his non-attorney public defender, Tolib Yakubov, then-chair of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan, who now lives in exile. A week before the sentencing, in a private conversation at the prison with Yakubov, he described how he had been tortured and pressured into signing a false confession.

Formonov is currently held at strict-regime Jaslyk prison (a violation of the terms of his verdict which specified that he be put into a "general" regime prison). Formonov has alleged he was tortured since being placed there, including being stripped of his overclothing and left in an unheated punishment cell for 23 days in January 2008, when temperatures reached approximately -20 C. More recently, Formonov told his family that on November 26, 2010, he and six cellmates in his brigade were placed in a punishment cell for 10 days. Before he was locked up, prison officers reportedly pressured Formonov into signing a document under threats that the rest of his brigade would be beaten if he refused.

Formonov's family told Human Rights Watch that he has been repeatedly prevented from being eligible for amnesty because the authorities bring charges of violations of the prison regime against him. The alleged violations included such actions as "helping prisoners write appeals," although Formonov says he was never in possession of a pen and at most only spoke to others about how to appeal their sentences.

Nosim Isakov

Isakov (b. 1966) is a member of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan who monitored human rights abuses in Jizzakh city.

Isakov was arrested on October 27, 2005, and charged with hooliganism on the basis of a neighbor's written complaint stating that he exposed himself in public to his neighbor's teenage daughter. Isakov's family and fellow human rights defenders found the accusation particularly shocking and offensive because he is a pious Muslim. At his trial, which began December 15, 2005, Isakov maintained his innocence and told the judge that while in pre-trial detention he had been beaten on his head with a bottle filled with water.

On December 20, 2005, Isakov was handed an eight-year prison sentence on multiple charges including hooliganism and extortion. According to local sources, Isakov is serving his sentence at Karshi Prison and his family members have been warned not to speak to anyone about him.

Gaibullo Jalilov

Jalilov (b. 1964) is a Karshi-based human rights defender who has been a member of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan since 2003. His work has focused on the crackdown on independent Muslims in the Kashkadarya region of Uzbekistan. At the time of his arrest in September 2009, he reportedly had collected information on over 200 arrests of independent Muslims in the region.

On January 18, 2010, in a trial that did not adhere to fair trial standards, the Kashkadarya District Criminal Court sentenced Jalilov to nine years in prison on fabricated charges of anti-constitutional activity, production and distribution of banned material, and membership in a banned religious organization. On March 9, 2010, the nine-year sentence was upheld on appeal. Jalilov was brought to the hearing with a swollen eye, suggesting that he recently had been ill-treated in custody.

Just seven months after his original conviction, on August 4, 2010, Jalilov was re-sentenced to 11 years, one month and five days on new criminal charges, allegedly on the basis of new evidence, in a trial that did not meet fair trial standards. Jalilov is serving his sentence in a prison in Zangiyota district, not far from Tashkent.

After a two-day visit in January 2011, Jalilov's wife told Human Rights Watch that since his arrest, Jalilov has repeatedly been tortured and ill-treated, including by being beaten with a nightstick that left him nearly deaf in both ears. His family also reported that Jalilov's lungs cause him pain (Jalilov has a previous lung condition) and that he is suffering from vertebral hernia.

On May 3, Jalilov called his wife to tell her that starting April 25, he spent approximately one week at the prison clinic in Tashkent because of a bad cough that caused him to have serious difficulty breathing, and requested that his wife bring medicines to their next visit in early June. Jalilov is in urgent need of appropriate medical care.

Alisher Karamatov

Karamatov (b. 1968) is an active member of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan in Gulistan, in Syrdaryo province who along with fellow defender Azam Formonov monitored violations of social and economic rights, in particular the rights of farmers and the disabled.

Karamatov was arrested on April 29, 2006, and sentenced on June 15, 2006 to nine years in prison on fabricated extortion charges following a trial that independent observers determined was unfair. According to his public defender, Karamatov confessed to the charges after being tortured, including being beaten on the soles of his feet and suffocated with a gas mask.

Karamatov's wife told Human Rights Watch that he has been in very poor health since he was put in prison. In October 2008, Karamatov was transferred to the prison clinic 64/18 where he was diagnosed with an advanced form of tuberculosis in both lungs. Since January 2011, he has been serving his sentence in prison colony UYa 64/49 in Karshi. After his wife visited him in early April, she reported that Karamatov has continued to lose weight and is very thin, has developed sores all over his body and wakes up with traces of blood in his mouth.

Prison officials have repeatedly accused Karamatov of violating internal prison rules to render him ineligible for amnesty or early release. His alleged violations include ‘saying prayers' and ‘wearing a white shirt'. Previously, on December 30, 2008, when Karamatov refused to sign a document attesting a breach of the prison regime, prison guards reportedly escorted him outside, took off his hat and jersey, and made him stand in freezing temperatures for nearly four hours in order to force him to sign the document.

On April 25, 2011, Karamatov's wife appealed to the office of the Ombudsman requesting that Karamatov be released on medical grounds due his "critical health condition."

Jamshid Karimov

Karimov (b. 1968) is an independent journalist from Jizzakh and vocal critic of the government's policies who regularly published articles on the internet, including on Uznews.net.

Karimov disappeared on September 12, 2006, while attempting to visit his mother at the Jizzakh Province Hospital. Soon thereafter Karimov was forcibly admitted to the Samarkand Psychiatric Hospital where according to unconfirmed reports, he was subjected to forcible treatment with antipsychotic drugs. There is no medical basis for Karimov's confinement or treatment, and it is widely believed that he is being held for no reason other than his journalistic activities.

Human Rights Watch has received worrying reports indicating that Karimov's family has been harassed and intimidated by the authorities and warned not to speak with anyone about his case. In late spring 2008 Karimov's mother passed away and he was allowed to attend the funeral and to be with his family for five days, but was instructed not to contact anyone outside the immediate family during this time.

Norboi Kholjigitov

Kholjigitov (b. 1953) is a member of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan in Samarkand province who defended farmers' rights, assisting farmers fighting expropriation of their farms. After working as the director of two state-owned farms he established his own farm, called Free Peasants, in 2004, and supported the poor.

Kholjigitov was arrested on June 4, 2005 and sentenced on October 18, 2005 to 10 years in prison on fabricated charges of extortion and slander. Since his imprisonment, Kholjigitov has faced ill-treatment and harassment by prison authorities, particularly after sending a complaint to the Supreme Court of Uzbekistan in November 2008. Prison officials have reportedly threatened him with transfer to a psychiatric clinic if he continues to file complaints. He is serving his sentence in prison colony UYa 64/49 in Karshi.

According to Kholjigitov's family, who met with him twice in recent months, Kholjigitov's health continues to progressively deteriorate. Kholjigitov suffers from a severe form of diabetes. He has lost more weight and has great difficulty walking. He has also apparently lost partial control of his right arm and legs due to complications from diabetes and has lost feeling in his feet. All of his teeth have fallen out, and he reportedly has stomach problems as he is unable to fully chew his food. His wife reported that he was unable to sit up as he has sores on his lower backside.

Kholgijitov reported that prison authorities have ignored his repeated requests to be transferred to the prison clinic in Tashkent for medical treatment. He is in urgent need of appropriate medical care.

Abdurasul Khudainasarov

Khudainasarov (b. 1956) is the head of the Angren branch of the human rights organization Ezgulik where his work focused on fighting corruption in the police and security forces.

Khudainasarov was arrested on July 21, 2005 and sentenced on January 12, 2006, to nine and one-half years in prison on fabricated charges of extortion, fraud, abuse of power, and falsification of documents. In a letter to his lawyer, Khudainasarov complained about beatings and ill-treatment he was subjected to the day after his trial ended. According to the letter, Khudainasarov was also put in a punishment cell the day after the verdict was issued in retribution for not confessing during the trial.

Khudainasarov is serving his sentence at a prison colony in Bekabad. His relatives reported to Human Rights Watch that he has suffered torture and ill-treatment in prison. Khudainasarov has filed complaints with the prosecutor's office and went on a temporary hunger strike to protest his ill-treatment. According to his wife, Khudainasarov attempted suicide in early fall 2008 and was rescued by fellow inmates. His wife was able to visit with him in early April 2011 and reported that he looked pale and weak, that he suffers frequent headaches and rheumatism in his legs, and that his nervous system is damaged.

Ganihon Mamatkhanov

Mamatkhanov (b. 1951) is a Ferghana-based human rights defender affiliated with the group Committee for the Protection of Individual Rights. He works on the protection of social and economic rights, including the rights of farmers, a number of whom were the victims of land confiscation in 2009. Before his arrest, Mamatkhanov regularly provided commentary on the human rights situation in Ferghana to Radio Ozodlik, the Uzbek branch of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Authorities arrested Mamatkhanov on October 9, 2009, under circumstances that appear to have been staged to frame him. He was sentenced to five years in prison on November 25, 2009, on fabricated charges of fraud and bribery. His trial was marred by serious procedural violations. Witnesses reportedly claimed that the investigator had instructed them how to act and what to say before and after Mamatkhanov's arrest.

Mamatkhanov's five-year prison sentence was converted to four and one-half years in a penal colony (koloniya poseleniya) on appeal at the Ferghana Regional Court in mid-January 2010. However, after allegedly violating the terms of his imprisonment in the penal colony, Mamatkhanov was transferred to a general regime prison in the Navoi region in spring 2010.

During a visit in January 2011, Mamatkhanov complained to his family of heart pain and bouts of high blood pressure. In October 2009, not long after he was detained, Mamatkhanov reportedly suffered two heart attacks while in detention.

Habibulla Okpulatov

Okpulatov (b. 1950) is a member of the Ishtikhan District Branch of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan and worked as a teacher in a school in Samarkand until his arrest on June 4. 2005. He was tried along with fellow human rights defender Norboi Kholjigitov by the Samarkand Regional Court and on October 18, 2005, was sentenced to six years in prison. This sentence was later reduced to four years under amnesty. Okpulatov is serving his sentence in prison colony 64/45 in Almalyk.

On September 30, 2009, Okpulatov was sentenced to an additional three years and eight days in prison by the Navoi City Criminal Court for alleged violations of prison regulations. The verdict stated that the court hearing was open to the public, but neither Okpulatov's relatives nor his lawyer were informed of the date of the trial, which took place in the prison.

After a visit with Okpulatov in late January 2011, his family reported there were some improvements in his health and that he had gained some weight, although his right leg is still debilitated. He told his family that allegations of prison regime violations continue to be brought against him, most recently in December 2010, when he was accused of using a dirty towel.

Yuldash Rasulov

Rasulov (b. 1969) has been a member of the Kashkadarya branch of the Human Rights Society of Uzbekistan since 2002. He worked to defend the rights of people persecuted for their religious beliefs and affiliations, especially those whose religious practice falls beyond the confines of state-sponsored Islam.

Rasulov was arrested in April 2007 sentenced in October 2007 to 10 years in prison on charges that included alleged anti-constitutional activity and membership in a banned religious organization. He is being held in prison colony No. 64/25 in Karabulbazar in the Bukhara region.

Authorities had previously brought politically motivated charges against Rasulov, sentencing him in September 2002 to a seven-year prison terms for attempting to overthrow the constitutional order, distributing "extremist" literature and membership in a banned religious organization. However, the evidence presented against Rasulov in court only showed that he prayed five times a day and had listened to tapes on Islam commonly available in the mid-1990s. Rasulov stated at trial that self-incriminating statements about his alleged involvement in "extremist" activities were made after he had been pressured. He was released after spending roughly seven months in detention.

Dilmurod Saidov

Saidov (b. 1962) is an independent journalist who has worked to expose corruption, abuse of power, and the general social and economic situation in the Samarkand region. His articles have been published in many local newspapers, as well as by internet new agencies Voice of Freedom and Uznews.net, among others. Saidov is a member of the Tashkent Regional Branch of Ezgulik, and since 2004 had been actively helping farmers defend their rights in the Samarkand region.

Saidov was arrested on February 22, 2009 at his home in Tashkent on fabricated charges of extortion. On July 30, 2009, after a flawed investigation and a trial riddled with procedural violations, the Tailak District Court in Samarkand sentenced Saidov to 12 and one-half years in prison.

Saidov's sentence has been upheld twice on appeal. During a meeting with his lawyer in late February 2010, Saidov asked him to submit a written statement he had prepared to the Supreme Court, but the document was confiscated by prison authorities as his lawyer tried to leave their meeting. Saidov told his family that he was later "punished."

In February 2010, Saidov was transferred to prison clinic UYa 64/18 in Tashkent to receive medical treatment (Saidov suffers from an acute form of tuberculosis), but according to his family, sometime in late summer 2010, Saidov was transferred back to prison colony UYa 64/36 in Navoi.

On August 11, 2010, Saidov's family made a direct appeal to the Ombudsperson for Human Rights Rashidova who met with the family, promised to "study the situation" and then later sent a written response on Nov. 9, 2010 to the family saying that her office had no jurisdiction over the matter. On February 8, 2011 his family tried again to have Saidov's case reviewed, , but in mid-March they received a response from the Supreme Court dismissing their request.

In December 2010, Saidov's relatives reported to Human Rights Watch that authorities had accused Saidov of multiple prison regime violations preventing him from being eligible for the 2010 amnesty. They also fear Saidov is being forced to take psychotropic drugs or other medications which cause him to be disoriented during prison visits. According to Saidov's relatives' Saidov "has become a skeleton."

When a relative visited the prison on April 27, prison authorities told him that Saidov had been put into a punishment cell for allegedly violating prison regulations, but would not say which one.

In another tragedy for the imprisoned journalist, Saidov's wife, Barno Djumanova, and the couple's six-year-old daughter, Rukhshona, died in an automobile accident on November 5, 2009, on the Tashkent-Samarkand highway. They had travelled to Kiziltepe to deliver Saidov's passport to the prison administration.

Akzam Turgunov

Turgunov (b. 1952) founded the human rights group Mazlum and is a member of the opposition political party ERK. He is an advocate for the rights of political and religious prisoners and speaks out against torture, helping others fight the police system. In the months leading up to his arrest on July 11, 2008, Turgunov had been working in Karakalpakstan as a public defender in a number of sensitive cases.

On October 23, 2008, the Amurdarinskii court in Manget, Karakalpakstan, sentenced Turgunov to 10 years in prison on fabricated charges of extortion. Serious due process violations denied Turgunov a fair and impartial trial and he was tortured in custody. On July 14, 2008 while he was in the investigator's office writing a statement, someone poured boiling water down his neck and back, causing him to lose consciousness and sustain severe burns. Authorities ordered an investigation into Turgunov's torture only after he removed his shirt during a court hearing on September 16 to show the scars from the burns, which covered a large portion of his back and neck. The subsequent forensic medical exam, however, concluded that his burns were minor and did not warrant any action.

Turgunov's family told Human Rights Watch that since he was imprisoned, Turgunov has lost a significant amount of weight and is in very bad health. Turgunov is almost 60 years old, but is forced to work multiple shifts at a brick factory in the prison. He continues to complain of severe leg pain as a result of this work, for which he is not given appropriate treatment.

His family visited him in mid-April 2011 and reported that Turgunov is frustrated that his efforts to have his case reviewed have not brought about any results. According to his family, at least once a month Turgunov sends complaints to various government organs in Tashkent, including to the Supreme Court, the Prosecutor General and the Ombudsman, requesting that his case be reviewed.

HRW,

HRW,  Uzbekistan,

Uzbekistan,  prtisoners

prtisoners